If you are interested in having a traditional Jewish henna ceremony, for a marriage or for any other happy occasion, or interested in having me speak to a group about Jewish henna traditions, please contact me!

See here for an overview of Jewish henna traditions in general, and Jewish henna in Israel today.

This information is the result of my own research. Please do not copy this information without proper citation.

See here for an overview of Jewish henna traditions in general, and Jewish henna in Israel today.

This information is the result of my own research. Please do not copy this information without proper citation.

Jewish Henna Traditions in Yemen, Aden, and the Hadhramaut

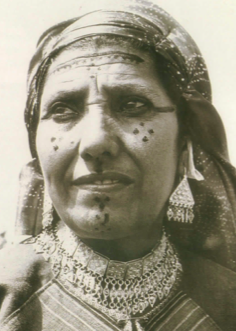

Rural Yemenite bride after 'aliya to Israel, mid-20th century.

The henna traditions of the Jewish communities of Yemen are among the most well-documented of any Jewish community; we have a comparatively large number of historical sources, and we know more about the regional variations among different communities in Yemen than we do for any other community (regional variations in general among Yemenite Jews are pronounced, perhaps due to the distance and relative difficulty travelling between villages; recall, also, that Aden and the Hadhramaut were not part of Yemen until 1967, and so their Jewish communities were also fairly isolated from mainstream Yemenite Jews). Among Yemenite Jews, henna ceremonies were an important part of the community’s ritual life. Like many other Jewish communities in the Diaspora, henna was applied for rites of passage and lifecycle ceremonies.

Henna was applied in daily life as a cosmetic; women would dye their palms, feet, nails, and hair, and men would dye their hair, beards, and sometimes even their hands. Generally, in daily life, the henna was not patterned, but merely spread over the hands and feet. Sometimes a simple string resist would be used to create a kind of netted pattern. In parts of south Yemen and the Hadhramaut, Jewish women would apply henna after their monthly visit to the miqve [ritual bath], one of several cultural signals (including other cosmetics and clothing) that indicated that they were now in a period of ritual purity. Henna was also used by Jewish women and girls in Yemen and Aden to beautify themselves for holidays, including Purim and Sukkot; unmarried girls were allowed only to henna their hands, because hennaed feet were seen as the prerogative of married women.

Henna was often used in conjunction with another cosmetic, a black gall ink known variously as nagsh/ naqsh, kheṭuṭ, sukreghe, or khiḍab. In some parts of Yemen, this was made along with the henna; in other areas, the ink was purchased ready-made from the neighbouring Muslim communities.

Henna was applied in daily life as a cosmetic; women would dye their palms, feet, nails, and hair, and men would dye their hair, beards, and sometimes even their hands. Generally, in daily life, the henna was not patterned, but merely spread over the hands and feet. Sometimes a simple string resist would be used to create a kind of netted pattern. In parts of south Yemen and the Hadhramaut, Jewish women would apply henna after their monthly visit to the miqve [ritual bath], one of several cultural signals (including other cosmetics and clothing) that indicated that they were now in a period of ritual purity. Henna was also used by Jewish women and girls in Yemen and Aden to beautify themselves for holidays, including Purim and Sukkot; unmarried girls were allowed only to henna their hands, because hennaed feet were seen as the prerogative of married women.

Henna was often used in conjunction with another cosmetic, a black gall ink known variously as nagsh/ naqsh, kheṭuṭ, sukreghe, or khiḍab. In some parts of Yemen, this was made along with the henna; in other areas, the ink was purchased ready-made from the neighbouring Muslim communities.

The bridal henna traditions of Yemenite Jews are some of the most well-known Jewish bridal henna traditions; however, the ceremony as practiced today is very different than its traditional predecessor. Furthermore, bridal henna traditions varied wildly from region to region in Yemen, and it was only in Israel that one standardized “Yemenite” henna ceremony was created.

|

In rural areas, the bride and groom were hennaed simply, with a solid wash of henna from fingertip to wrist (or further up, sometimes as far as the elbow) and on the feet from the soles to the ankles. Sometimes simple patterns were made by applying the henna in broad stripes or dots. Among Habbani Jews, from the south-eastern Hadhramaut, the pattern was commonly a ring of henna in the centre of the palm, with a dot in the centre, and stripes across the finger. The Habbani community remained fairly insular after their immigration to Israel, and so this pattern has been preserved and is still practiced, even today, among Habbani brides in Israel. Unfortunately, this is not true of any other Yemenite community.

|

It is the Sana‘i community, however, which had the most elaborate and time-consuming henna traditions for their brides. The hennaing of the brides lasted between two to four days; the process began, generally on a Monday or Tuesday, with a solid coat of henna from the fingertips up to the elbow, and the feet as well. The bride’s henna was wrapped up in special cloths known as meḥani, to prevent the henna from dirtying their clothes or sheets. The henna was left on for a few hours, and then washed off.

|

The next day, the professional artist, known as the shar‘a, came with a special waxy mixture of resin, myrrh, frankincense, and iron sulfate. This mixture was heated in a small pan over a fire until it was like molten wax, and then dripped (with a quill, reed pen, or kohl stick) onto the bride’s hands and feet in specific patterns. Generally the fingers were decorated with an ear of grain, and the palms and feet with bands of geometric patterns similar to those used in Yemenite embroidery, with zigzag lines, netting, and dots. Sometimes the design was centred around a star or circular shape.

Unfortunately, no photos have survived of this technique, to my knowledge (if you know of any, please contact me!). We can only try to reconstruct what these patterns may have looked like from written descriptions and surviving examples of Yemenite Jewish textiles and ebroidery. |

After the wax was applied (this step was generally known as nagsh/naqsh), sometimes a second coat of henna was applied and left on overnight. If so, they would remove the henna the next morning and continue to the next step; if not, they would proceed right to the next step, known as teṭrufa or shaḍḍar. This was a darkening of the henna with a caustic mixture of ammoniac (shaḍḍar) and potash (ḥuṭma). This paste was spread over the hands and feet on top of the wax, and left on for about one hour. It was then rubbed off; the exposed henna would turn a deep greenish-black, while the areas protected by the wax retained their orange-red shade, so the bride’s hands and feet were decorated with reddish designs against a dark greenish-black background.

|

Brides would have this done up to their elbows, while other women (married or unmarried) would just do their palms. Little girls and widows would decorate themselves only with henna. After this whole process, the bride’s hands, feet, and face would be decorated with the black gall ink known as nagsh/ naqsh, kheṭuṭ, sukreghe, or khiḍab. Yemenite Jewish brides, and women in general, also decorated themselves with other cosmetics, including turmeric (hurud) and indigo (nil).

The groom had a separate henna ceremony, but was not decorated with naqsh or teṭrufa as was the bride. As in Persian communities, it was the chief rabbi (mori) who would have the honour of applying the first henna to the groom, followed by the groom’s father, and then the various men of the community would offer gifts and money in return for the privilege of hennaing the groom. |

Travellers to Yemen in the 19th and 20th centuries recorded their observations of Jewish henna ceremonies, both of the groom and the bride, and descriptions of Yemenite Jewish communities living in Israel in the early 20th century show that henna ceremonies were performed much in the same way as in Yemen. These descriptions show that the technique of hennaing complicated patterns over a period of several days was practiced by Jewish communities in both Yemen and Israel until the mid-20th century. Today, in Israel many Jews of Yemenite origin still perform henna ceremonies before marriage, but the henna has been reduced to a mere circular smear in the palm. Brides will often demonstrate a ‘fashion show’ of various costumes from different areas in Yemen, but the most frequent costume worn is the grand headdress, the tishbuk lulu, which has become a symbol of Yemenite culture in general.

Sources and References:

Abdar, Carmela. 2008a Tishbuk lulu - ‘aṭeret peninim: ‘al tilboshet hakala veṭipuaḥ gufah betiqsei haḥatuna shel yehudei Ṣana‘ [Tishbuk lulu - A Crown of Pearls: on the clothing of the bride and the ornament of her body in the wedding ceremonies of the Jews of Sana‘]. In Ma‘ase roqem: halevush vehatakhshiṭ bamesoret yehudei Teiman [A Weaver’s Work: Dress and jewelry in the tradition of the Jews of Yemen], ed. Carmela Abdar.

Abdar, Carmela. 2008b “Hitpa’ari behopha‘atekh velo biyiḥusekh”: minhagei halevush shel hayehudiyyot baTeiman hataḥtona [“Beautify Yourself in Appearance, Not in Relations”: customs of dress of Jewish women in Lower Yemen]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. Carmela Abdar.

Abdar, Carmela. 2008c “Nesikhim me’ereṣ qedem”: minhagei halevush shel hayehudiyya miḤabban [“Princes from an Eastern Land”: customs of dress of the Habbani Jewish woman]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. Carmela Abdar.

Bar‘am-Ben Yosef, No‘am. 2008 “Ma‘ase roqem”: simlat hayehudiyya miḌala veriqmata [“A Weaver’s Work”: the dress of the Jewish woman from Ḍala and its embroidery]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. by Carmela Abdar.

Ben-David, Aharon. 2008 Beit ha’even: halikhot yehudei ṣefon Teiman [The House of Stone: the ways of the Jews of northern Yemen].

Brauer, Erich. 1934 Ethnologie der jemenitischen juden [Ethnology of the Yemenite Jews].

David, Moshe. 2008 “Gali li et panekh”: halevush, hatakhshiṭ vetipuaḥ haguf shel hayehudiyyot miBayḥan [“Reveal Your Face to Me”: dress, jewelry, and body care of Jewish women from Bayḥan]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. by Carmela Abdar.

Dori, Zecharia. 1982 Hapukh vehakofer: hakeḥul vehaḥinna [The Pukh and the Kofer: kohl and henna].

du Couret, Louis. 1859 Les Mystères du Désert: Souvenirs de Voyages en Asie et en Afrique [The Mysteries of the Desert: Memories of Voyages in Asia and Africa].

Goldschmidt, Dani. 2008 Mimesoret lemoderna: signon halevush shel yehudei ‘Aden [From tradition to modernity: the style of dress among the Jews of ‘Aden]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. Carmela Abdar.

Kapah [Qafih], Yosef. 1961 Halikhot Teiman [The Ways of Yemen].

Klein, Aviva. 1979 Minhagei haḥatuna shel neshot Rada‘ [Wedding Customs of the Women of Rada‘]. Yeda‘ ‘Am, No. 19.

Levi Nahum, Yehuda. 1962 Miṣefunot yehudei Teiman [Secrets of the Jews of Yemen]. Ed. by Shimʿon Garidi.

Maysels, Theodore. 1941 Henna Night in Shaarei Pinna: A Yemenite Wedding. The Palestine Post, Tuesday May 6.

Qorah, ‘Amram. 1954 Sa‘arat Teiman [Yemenite Storm]. Ed. by Shim‘on Garidi.

Ratzhaby, Yehuda. 1963 Shirei ḥatuna beRada‘ shebeTeiman [Wedding Songs from Rada‘ in Yemen]. Mahanayim, No. 83.

Saphir, Jacob. 1866 Even Sappir: admat Ḥam (masa‘ Miṣrayim), Yam Suf, ḥadrei Teiman, mizraḥ Hodu kulo, ereṣ haḥadasha Ostraliya veshuvato haramata Yerushalayim [The Sapphire Stone: the land of Ham (a journey to Egypt), the Red Sea, the chambers of Yemen, all of East India, the new land of Australia, and an ascending return to Jerusalem].

Sémach, Yomtob. 1910 Une Mission de L’Alliance au Yémen [A Mission of the Alliance to Yemen].

Sharaby, Rachel. 2006 The Bride’s Henna Ritual: Symbols, Meanings and Changes. In Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies and Gender Issues, Vol. 11.

Tshernovits, Nahum. 1984 Minhagei nissu’in shel yehudim biṣefon mizraḥ Teiman [Wedding customs of Jews in north-east Yemen]. ‘Am va-areṣ A, Vol. 19.

Abdar, Carmela. 2008b “Hitpa’ari behopha‘atekh velo biyiḥusekh”: minhagei halevush shel hayehudiyyot baTeiman hataḥtona [“Beautify Yourself in Appearance, Not in Relations”: customs of dress of Jewish women in Lower Yemen]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. Carmela Abdar.

Abdar, Carmela. 2008c “Nesikhim me’ereṣ qedem”: minhagei halevush shel hayehudiyya miḤabban [“Princes from an Eastern Land”: customs of dress of the Habbani Jewish woman]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. Carmela Abdar.

Bar‘am-Ben Yosef, No‘am. 2008 “Ma‘ase roqem”: simlat hayehudiyya miḌala veriqmata [“A Weaver’s Work”: the dress of the Jewish woman from Ḍala and its embroidery]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. by Carmela Abdar.

Ben-David, Aharon. 2008 Beit ha’even: halikhot yehudei ṣefon Teiman [The House of Stone: the ways of the Jews of northern Yemen].

Brauer, Erich. 1934 Ethnologie der jemenitischen juden [Ethnology of the Yemenite Jews].

David, Moshe. 2008 “Gali li et panekh”: halevush, hatakhshiṭ vetipuaḥ haguf shel hayehudiyyot miBayḥan [“Reveal Your Face to Me”: dress, jewelry, and body care of Jewish women from Bayḥan]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. by Carmela Abdar.

Dori, Zecharia. 1982 Hapukh vehakofer: hakeḥul vehaḥinna [The Pukh and the Kofer: kohl and henna].

du Couret, Louis. 1859 Les Mystères du Désert: Souvenirs de Voyages en Asie et en Afrique [The Mysteries of the Desert: Memories of Voyages in Asia and Africa].

Goldschmidt, Dani. 2008 Mimesoret lemoderna: signon halevush shel yehudei ‘Aden [From tradition to modernity: the style of dress among the Jews of ‘Aden]. In Ma‘ase roqem [A Weaver’s Work], ed. Carmela Abdar.

Kapah [Qafih], Yosef. 1961 Halikhot Teiman [The Ways of Yemen].

Klein, Aviva. 1979 Minhagei haḥatuna shel neshot Rada‘ [Wedding Customs of the Women of Rada‘]. Yeda‘ ‘Am, No. 19.

Levi Nahum, Yehuda. 1962 Miṣefunot yehudei Teiman [Secrets of the Jews of Yemen]. Ed. by Shimʿon Garidi.

Maysels, Theodore. 1941 Henna Night in Shaarei Pinna: A Yemenite Wedding. The Palestine Post, Tuesday May 6.

Qorah, ‘Amram. 1954 Sa‘arat Teiman [Yemenite Storm]. Ed. by Shim‘on Garidi.

Ratzhaby, Yehuda. 1963 Shirei ḥatuna beRada‘ shebeTeiman [Wedding Songs from Rada‘ in Yemen]. Mahanayim, No. 83.

Saphir, Jacob. 1866 Even Sappir: admat Ḥam (masa‘ Miṣrayim), Yam Suf, ḥadrei Teiman, mizraḥ Hodu kulo, ereṣ haḥadasha Ostraliya veshuvato haramata Yerushalayim [The Sapphire Stone: the land of Ham (a journey to Egypt), the Red Sea, the chambers of Yemen, all of East India, the new land of Australia, and an ascending return to Jerusalem].

Sémach, Yomtob. 1910 Une Mission de L’Alliance au Yémen [A Mission of the Alliance to Yemen].

Sharaby, Rachel. 2006 The Bride’s Henna Ritual: Symbols, Meanings and Changes. In Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies and Gender Issues, Vol. 11.

Tshernovits, Nahum. 1984 Minhagei nissu’in shel yehudim biṣefon mizraḥ Teiman [Wedding customs of Jews in north-east Yemen]. ‘Am va-areṣ A, Vol. 19.

Pictures from:

Abdar, Carmela (ed.). 2008 Ma‘ase roqem: halevush vehatakhshiṭ bamesoret yehudei Teiman [A Weaver’s Work: Dress and jewelry in the tradition of the Jews of Yemen].