If you are interested in having a traditional Jewish henna ceremony, for a marriage or for any other happy occasion, or interested in having me speak to a group about Jewish henna traditions, please contact me!

See here for an overview of Jewish henna traditions in general, and Jewish henna in Israel today.

This information is the result of my own research. Please do not copy this information without proper citation.

See here for an overview of Jewish henna traditions in general, and Jewish henna in Israel today.

This information is the result of my own research. Please do not copy this information without proper citation.

Jewish Henna Traditions in Algeria

While the henna traditions of the Jews of Morocco are fairly well-established in literature, there is less known about henna traditions practiced by other Jewish communities in North Africa, in the modern countries of Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya.

In the past, henna was an important part of daily ornament among Algerian Jews. Colonial travellers in Algeria record that Jewish women dyed their hands and feet weekly with henna, and that Jewish mothers would dye the hair of their children (both male and female) with henna, believing that it kept away lice.

|

There were professional henna artists among Algerian Jews; a henna artist was known as a ḥarqassa. The term comes from the word ḥarqus, a type of black gall ink commonly used in North Africa to adorn faces and hands. We can assume that the original meaning of ḥarqassa was someone who applied ḥarqus, but among the Jews the usage shifted to refer to a henna artist (we might presume that the same person may have applied both ḥarqus and henna, but while ḥarqus was used by Jews, henna was certainly more common).

The ḥarqassa created the henna patterns with her fingers, by taking a lump of henna, rolling it into a thin thread, laying it onto the skin, and then repeating. The patterns were fairly simple and geometric. The ḥarqassa would traditionally henna hands and feet. In more rural Jewish communities in Algeria, extensive henna coverage remained popular, but in the early 20th century the Jews in the cities were influenced by French fashion and preferred not to have too much visible henna. When getting married à la Française (a civil wedding) they would often ask the ḥarqassa to henna only their feet, up to the edge of the ankle so that it would be covered by their shoes and no-one would see. |

Like in Morocco, henna was used to mark rites of passage and lifecycle events. Jews in southern Algeria performed a ritual (actually a series of rituals), known as kittab, for boys who were beginning their formal education: all the boys, around the age of five, were hennaed and dressed in fine clothing. Their families hosted a feast in their homes, and the boys were honoured in the synagogue with a special procession. This ritual was also practiced by some Jewish communities in Morocco.

Henna was also used in Algeria, as it was in Morocco, to celebrate a boy's becoming bar miṣwa. In the evening before the celebration in synagogue, there would be a festive meal with guests in the house. The men would take the boy to the hammam [public bath], and then bring him back with songs and drumming. When they arrived home, he would be seated in a place of honour. The barber came, and cut the hair of the bar miṣwa boy and all the young boys his age. Then his hands were hennaed: sometimes a family member would do it, and sometimes they would bring the ḥarqassa. After the boy was hennaed, the other guests were hennaed as well.

The wedding period began with the engagement, when the couple was brought to the rabbi and declared in front of two witnesses that they wished to marry. The parents of the bride and groom brought each other presents, and the groom's mother applied henna to the bride and placed a gold coin in her palm, which the bride kept. It was generally a small family event, and the henna was applied by the bride's mother-in-law rather than the ḥarqassa.

The next henna ceremony was held one week before the wedding, after the bride returned from the hammam, where her hair was hennaed. This ceremony, where the bride's dowry was displayed, was known as tahniyya, which literally means 'relief' or 'joy'; it was thought to represent the joy of the family that their children were finally getting married (in reality, the etymology is probably from a softening of the word taḥniyya, which means 'the hennaing'). After the presentation of the fabrics, jewelry, dresses, and other items that constituted the dowry, the henna was brought into the room in a silver bowl, with a lit candle in the middle, surrounded by eggs. The bride's mother-in-law would again place a gold coin in the bride's palm and henna over it, and the bride's henna would be tied up with coloured ribbons — pink in Constantine, red in other parts of Algeria. The family and friends would be hennaed as well, and there was a custom that the guests would remove their henna before leaving the house so that the happiness would stay with the bride.

The final henna ceremony was held the night before the wedding. The bride again went to the hammam, and was hennaed upon her return, this time by the professional ḥarqassa. It was traditional for the bride to have her hands hennaed up to the wrist and her feet up the ankle, but as noted, in recent years the custom declined in popularity due to French influence.

The wedding period began with the engagement, when the couple was brought to the rabbi and declared in front of two witnesses that they wished to marry. The parents of the bride and groom brought each other presents, and the groom's mother applied henna to the bride and placed a gold coin in her palm, which the bride kept. It was generally a small family event, and the henna was applied by the bride's mother-in-law rather than the ḥarqassa.

The next henna ceremony was held one week before the wedding, after the bride returned from the hammam, where her hair was hennaed. This ceremony, where the bride's dowry was displayed, was known as tahniyya, which literally means 'relief' or 'joy'; it was thought to represent the joy of the family that their children were finally getting married (in reality, the etymology is probably from a softening of the word taḥniyya, which means 'the hennaing'). After the presentation of the fabrics, jewelry, dresses, and other items that constituted the dowry, the henna was brought into the room in a silver bowl, with a lit candle in the middle, surrounded by eggs. The bride's mother-in-law would again place a gold coin in the bride's palm and henna over it, and the bride's henna would be tied up with coloured ribbons — pink in Constantine, red in other parts of Algeria. The family and friends would be hennaed as well, and there was a custom that the guests would remove their henna before leaving the house so that the happiness would stay with the bride.

The final henna ceremony was held the night before the wedding. The bride again went to the hammam, and was hennaed upon her return, this time by the professional ḥarqassa. It was traditional for the bride to have her hands hennaed up to the wrist and her feet up the ankle, but as noted, in recent years the custom declined in popularity due to French influence.

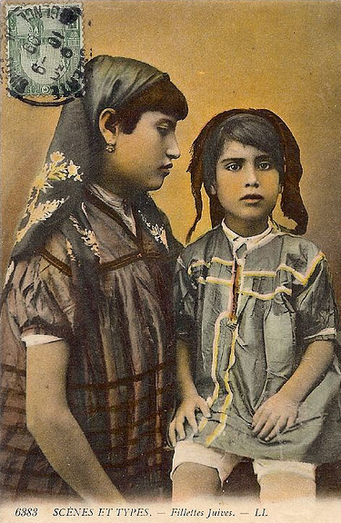

A hennaed Algerian Jewish dancer, early 20th century.

If an Algerian Jew was very ill, it was believed that they had offended one of the "underground spirits", i.e. the jnun. To remedy this, they would hold a special ceremony known as sulḥa or salḥa. They would keep the ill person in the house for eight days, and have them drink a special herbal beverage called sulḥa [sarsaparilla]. After eight days, they brought a troupe of non-Jewish musicians to play and dance and the ill person (whether male or female) would be hennaed on their hands and feet. They would then be brought to a place with naturally flowing water, where they would throw in the sulḥa, cakes made of semolina and honey, and the dried henna paste; they would ask God to protect and heal the afflicted person, and to forgive them any wrong they may have done. The musicians would play fast-paced music and the women would "dance the spirit out".

An Algerian woman described it as a kind of trance: “We would lose everything. We didn’t know where we were, really, not at all... And this black man [the non-Jewish musician/dancer] would [also] go into a trance, and dance, and then he would faint. When he fainted, we would say, ‘This is it, the jnun have left’”. This bears many resemblances to the zar cult, a system of spirit possession and trance healing practiced throughout North and East Africa and parts of Western Asia, which similarly uses henna to mark the participant at the centre of the ritual.

An Algerian woman described it as a kind of trance: “We would lose everything. We didn’t know where we were, really, not at all... And this black man [the non-Jewish musician/dancer] would [also] go into a trance, and dance, and then he would faint. When he fainted, we would say, ‘This is it, the jnun have left’”. This bears many resemblances to the zar cult, a system of spirit possession and trance healing practiced throughout North and East Africa and parts of Western Asia, which similarly uses henna to mark the participant at the centre of the ritual.

As in Morocco, henna was also used to protect people moving into a new home. The henna powder would be mixed with tea, and the paste was spread on the doorstep and in the corners, along with honey and milk. This was thought to bring prosperity and happiness to the new inhabitants.

Sources and References

Allouche-Benayoun, Joëlle. 1999 The Rites of Water for the Jewish Women of Algeria: Representations and Meanings. In Women and Water: Menstruation in Jewish Life and Law.

Briggs, Lloyd Cabot, and Norina Lami Guède. 1964 No More Forever: a Saharan Jewish town.

Grosberg, J. 1858 Jewish Miscellanies: Algeria. Church of England Magazine, Vol. 44.

Herber, Jean. 1929 Peintures corporelles au Maroc: les peintures au ḥarqus [Body painting in Morocco: paintings with ḥarqus]. Hespéris, Vol. 9 No. 1.

Rozet, Claude-Antoine. 1833 Voyage dans La Régence d’Alger, ou Description du Pays Occupé par l’Armée Française en Afrique [A Voyage in the Kingdom of Algeria, or, A Description of the Country Occupied by the French Army in Africa].

Zaccone, Victor-Joseph. 1865 De Batna à Tuggurt et au Souf [From Batna to Tuggurt and the Suf].

Briggs, Lloyd Cabot, and Norina Lami Guède. 1964 No More Forever: a Saharan Jewish town.

Grosberg, J. 1858 Jewish Miscellanies: Algeria. Church of England Magazine, Vol. 44.

Herber, Jean. 1929 Peintures corporelles au Maroc: les peintures au ḥarqus [Body painting in Morocco: paintings with ḥarqus]. Hespéris, Vol. 9 No. 1.

Rozet, Claude-Antoine. 1833 Voyage dans La Régence d’Alger, ou Description du Pays Occupé par l’Armée Française en Afrique [A Voyage in the Kingdom of Algeria, or, A Description of the Country Occupied by the French Army in Africa].

Zaccone, Victor-Joseph. 1865 De Batna à Tuggurt et au Souf [From Batna to Tuggurt and the Suf].