If you are interested in having a traditional Jewish henna ceremony, for a marriage or for any other happy occasion, or interested in having me speak to a group about Jewish henna traditions, please contact me!

See here for an overview of Jewish henna traditions in general, and Jewish henna in Israel today.

This information is the result of my own research. Please do not copy this information without proper citation.

See here for an overview of Jewish henna traditions in general, and Jewish henna in Israel today.

This information is the result of my own research. Please do not copy this information without proper citation.

Jewish Henna Traditions in the Levant

Ancient sources show that henna was grown and used in the Levant, and the medieval henna trade flourished along the Mediterranean coast. Colonial-era sources document the existence of henna traditions among Jewish communities in the Levant, but it appears that the henna ceremony fell out of practice in the early twentieth century. In my fieldwork, Jews from Aleppo and Damascus have all maintained that they did not hold a henna ceremony in their memory (one man did mention that they would send henna to the bride in the hammam). Some informants from Damascus mentioned that they themselves did not remember henna ceremonies but that they were common among the Jews in Qamishli (a rural area in the north of Syria).

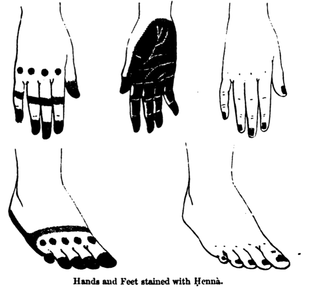

One of the earliest descriptions comes from the British physician Alex Russell, who recorded his life in Aleppo in the middle of the 18th century. He describes the use of henna by the natives of the city, equally common among the Turks [i.e. Muslim Ottomans], Christians, and Jews, and explains that "the common way is only to dye the tips of the fingers and toes, and some spots on the hands and feet, and leave them a dirty yellow colour, the natural tincture from the henna, which to a European looks very disagreeable", but "the more polite manner is to have the greatest part of the hands and feet stained in form of roses, and various figures, and the dye made of a very dark green. This however, after some days, begins to change, and at last looks as nasty as the other". In a footnote, he expands on the process of creating the henna patterns:

|

The method of applying the henna is thus. They take some of the henna in powder, and making it into a paste with water, roll or spin it out into small threads; then they take a piece of leaven, and with a rolling-pin roll it out into a very thin cake, which they cut out into proper forms, for covering the hands, feet, fingers, and toes; and upon this the threads of the henna-paste are placed in the forms they intend to imprint upon the parts. A piece of the henna-paste is applied to the tip of each finger and toe; and then the pieces of leaven-cake, prepared as above, are tied on to the different parts they are intended for, and suffered to remain there for two or three hours; at the expiration of which all is taken off, and the mark of the several figures made with the henna are found imprinted on the parts to which they were applied. They then cover the whole hands and feet with a paste made of wheat-flour, a small proportion of crude sal ammoniac, and a little quicklime, with a sufficient quantity of water, which in about half an hour turns all the parts that had been dyed before of a dirty red or yellow, with the henna, into a sort of black, or rather very dark green colour.

|

This darkening process uses a mixture of ammonia over the fresh stain, which will indeed darken a henna stain from a reddish-brown to a dark green or black; a similar technique was described in Egypt by Edward Lane in the late 19th century.

The use of patterned henna among the Jews of Aleppo specifically for the pre-wedding ceremony is recorded by Henri Guys, describing his experience of Jewish weddings in Aleppo in the mid 19th century. He writes that two or three days before the wedding, the groom sends a request to the parents of the bride, asking how much henna to prepare. He then instructs the henna artist (interestingly, a Muslim woman), who prepares a dough that she cuts in ribbons, squares, and small circles, paints with henna, and ties onto the fingers and palms with linen. This is kept until the next day and then removed. The henna offered to the bride is accompanied by a pair of kalchin (house-slippers without soles).

The French baron Fernand Schickler noted that Jewish women in Damascus dyed their hands with henna as part of their regular adornment, which he found very distasteful, as he writes: "Unfortunately, the Jewish women of Damascus disfigure themselves by covering their faces with make-up and their fingers with henna; they hide their cheeks under veritable sheets of rouge and paint on fantastic eyebrows; by these transformations, their original and unique aspect is lost in a general character of a revolting exaggeration".

Many authors similarly show strong Eurocentric prejudice and disapproval of non-European ideas of beauty; another author writes of Jewish women in Damascus that they “shew [sic] their bad taste, and disfigure themselves by this extraordinary painting of the eyebrows, which is always executed after the same fashion, and imparts a monotonous and almost comical expression to the faces of the women... As all the different natural shades of complexion are destroyed by painting the eyes, the cheeks, and the lips, all of them are more or less alike... [with their palms and nails] painted yellow with henna”.

The French baron Fernand Schickler noted that Jewish women in Damascus dyed their hands with henna as part of their regular adornment, which he found very distasteful, as he writes: "Unfortunately, the Jewish women of Damascus disfigure themselves by covering their faces with make-up and their fingers with henna; they hide their cheeks under veritable sheets of rouge and paint on fantastic eyebrows; by these transformations, their original and unique aspect is lost in a general character of a revolting exaggeration".

Many authors similarly show strong Eurocentric prejudice and disapproval of non-European ideas of beauty; another author writes of Jewish women in Damascus that they “shew [sic] their bad taste, and disfigure themselves by this extraordinary painting of the eyebrows, which is always executed after the same fashion, and imparts a monotonous and almost comical expression to the faces of the women... As all the different natural shades of complexion are destroyed by painting the eyes, the cheeks, and the lips, all of them are more or less alike... [with their palms and nails] painted yellow with henna”.

The negativity of this European attitude towards henna use may have encouraged its eventual abandonment. The Pharmaceutical Journal of Britain reported in 1873: “It is also interesting to note that the use of henna is on the decline, that appearing in the markets of North Syria being inferior in quantity and quality, and the import of 1872 not having found a ready or remunerative sale. The use of it is thoroughly an oriental custom, and although women are still seen with their hands and horses with their tails dyed with henna, its use is rapidly going out like other Eastern fashions, which are receding as those of Europe advance”.

Selma Duek Sutton, born in Aleppo, 1906, says the following about her wedding: “My marriage took place in 1922 - I was sixteen years old... The ceremonial swehnie, platters, were sent by the groom to the bride-to-be with perfume and silken robes and flowers. There was another tray sent - Sehneet il-Na’ish, this one contained other gifts, as well as a purse with some money... In my time henna was no longer in vogue”.

Selma Duek Sutton, born in Aleppo, 1906, says the following about her wedding: “My marriage took place in 1922 - I was sixteen years old... The ceremonial swehnie, platters, were sent by the groom to the bride-to-be with perfume and silken robes and flowers. There was another tray sent - Sehneet il-Na’ish, this one contained other gifts, as well as a purse with some money... In my time henna was no longer in vogue”.

Sources and References:

Beaton, Patrick. 1859 The Jews in the East (translation and expansion of Nach Jerusalem! [To Jerusalem!] by Ludwig Frankl).

Guys, Henri. 1854 Un Dervich Algérien en Syrie; peinture des moeurs musulmanes, chrétiennes et Israélites [An Algerian Dervish in Syria: a description of the customs of Muslims, Christians, and Jews].

Lane, Edward. 1860 An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, Written in Egypt during the years 1833, -34, and -35.

Pharmaceutical Journal of Britain. 1874 Aleppo Drugs. Pharmaceutical Journal of Britain, Saturday September 6, 1873.

Russell, Alexander. 1756 The Natural History of Aleppo, and Parts Adjacent, Containing A Description of the City, and the Principal Natural Productions in its Neighbourhood.

Russell, Alexander. 1794 The Natural History of Aleppo, and Parts Adjacent, Containing A Description of the City, and the Principal Natural Productions in its Neighbourhood. The Second Edition, Revised, Enlarged, and Illustrated with Notes.

Schickler, Fernand. 1863 En Orient: Souvenirs de voyage, 1858-1861 [In the Orient: Memories of a Voyage, 1858-1861].

Sutton, Joseph. 1979 Magic Carpet: Aleppo-In-Flatbush; The Story of a Unique Ethnic Jewish Community.

Sutton, Joseph. 1988 Aleppo Chronicles: the story of the unique Sephardeem of the ancient Near East - in their own words.

Guys, Henri. 1854 Un Dervich Algérien en Syrie; peinture des moeurs musulmanes, chrétiennes et Israélites [An Algerian Dervish in Syria: a description of the customs of Muslims, Christians, and Jews].

Lane, Edward. 1860 An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, Written in Egypt during the years 1833, -34, and -35.

Pharmaceutical Journal of Britain. 1874 Aleppo Drugs. Pharmaceutical Journal of Britain, Saturday September 6, 1873.

Russell, Alexander. 1756 The Natural History of Aleppo, and Parts Adjacent, Containing A Description of the City, and the Principal Natural Productions in its Neighbourhood.

Russell, Alexander. 1794 The Natural History of Aleppo, and Parts Adjacent, Containing A Description of the City, and the Principal Natural Productions in its Neighbourhood. The Second Edition, Revised, Enlarged, and Illustrated with Notes.

Schickler, Fernand. 1863 En Orient: Souvenirs de voyage, 1858-1861 [In the Orient: Memories of a Voyage, 1858-1861].

Sutton, Joseph. 1979 Magic Carpet: Aleppo-In-Flatbush; The Story of a Unique Ethnic Jewish Community.

Sutton, Joseph. 1988 Aleppo Chronicles: the story of the unique Sephardeem of the ancient Near East - in their own words.