If you are interested in having a traditional Jewish henna ceremony, for a marriage or for any other happy occasion, or interested in having me speak to a group about Jewish henna traditions, please contact me!

See here for an overview of Jewish henna traditions in general, and Jewish henna in Israel today.

This information is the result of my own research. Please do not copy this information without proper citation.

See here for an overview of Jewish henna traditions in general, and Jewish henna in Israel today.

This information is the result of my own research. Please do not copy this information without proper citation.

Jewish Henna Traditions in Morocco

Among Moroccan Jews, henna ceremonies were an important part of the community’s ritual life. Like many other Jewish communities in the Diaspora, henna was applied for rites of passage and lifecycle ceremonies, including rituals for birth, weaning, puberty, and marriage.

|

One such ceremony was held on the eighth night after the birth of a boy, the evening before his circumcision. Women would gather in the mother's house to sing, eat, and apply henna, while the men read selections from the Zohar [a mystical work in Aramaic believed to have protective qualities]. This night was thought to be the most perilous for the child, so these extra precautions were taken to protect it.

Another unique ceremony was known as kittab, and it was practiced in southern Morocco as well as in parts of Algeria. It was a passage ceremony welcoming small children into the beginning of their formal education, around the age of five. They would be hennaed and dressed in fine clothing, and taken to the synagogue in a grand procession, on the holiday of Shavu'ot. In the Jewish mystical tradition, Shavu'ot is seen as a symbolic marriage between the Torah and the people of Israel, and so the children entering the school system are seen as the brides and grooms. The little boys would be matched with little girls, and at the synagogue the rabbi would write them a wedding contract in honey on a piece of paper, which the children would then lick up gleefully. |

Among Jewish communities in the High Atlas Mountains, it was also common to hold a henna ceremony for children for such milestones as their weaning, their first haircut, or having grown five teeth.

|

Moroccan Jews, both in the South and in the North, held a special henna ceremony for boys on the evening before the celebration of their becoming bar miṣwa. In the morning, boy was taken to the hammam [public bath]; then the barber came and gave the boy a special haircut. That evening, their family held a festive meal in their home. The boy was presented with the tefillin [ritual phylacteries] and tallit [ritual shawl] that he would wear as an adult, and he gave a short speech about the assigned Torah portion for that week. The rabbi gave him a blessing and the boy's palms were hennaed.

Henna was used to celebrate holidays, and was used as a cosmetic and personal ornament. A British colonel recorded in 1842 that Jews in Taza, in the Middle Atlas, would henna their hands for Passover, and Nahum Slouschz, a famed Jewish scholar and educator, noted in the early 20th century that it was customary for Jewish women in the area of Ouarzazate, in southern Morocco, to henna their hands in honour of the Sabbath. |

|

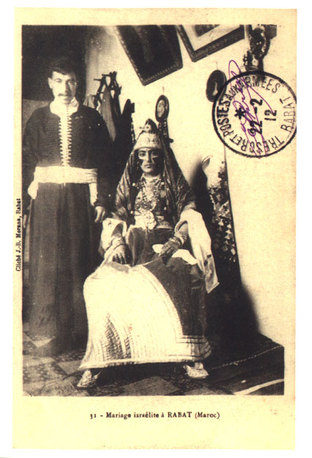

One of the most important henna ceremonies was in preparation for a wedding. In many Moroccan Jewish communities, they had more than one henna night: two, three, or even as many as eight! In one ceremony, henna was mixed into the bride’s hair, with cloves, sugar, and an egg (this was known as azmomeg). In another ceremony, the bride (and sometimes the groom) had their hands and feet hennaed. Henna was seen as both enhancing the beauty of the bride and also protecting her during her liminal state from the Evil Eye and other ominous spirits.

In some communities in Morocco, the henna was applied in specific patterns, by professional artists, with a needle, a quill, or a thin stick. The Jewish Italian traveller Samuel Romanelli wrote in 1792 that Jewish brides in Morocco had "strange designs" drawn on their face with a black dye (most likely ḥarqus, a type of gall ink) and on their hands with henna; his description is confirmed by the British physician William Lempriere, who wrote in 1793 that Jewish brides had "a variety of figures" drawn on their hands in henna with a needle. Alliance Israëlite Universelle teacher Isaac Benchimol wrote in 1888: "During the time [before the wedding day], the bride’s house is in great animation. It is essentially the 'day of the henna': the bride, along with all her female friends, cover their hands with henna, forming designs which, very frequently, are quite lovely. They hold their hands to the fire, and soon one sees the designs emerge in strong red colour." |

As far as we can tell, the designs were very similar to the patterns used by their Muslim neighbours. In early 20th-century Fes, Jewish women wrapped strings around the fingers to create resist designs (a similar technique was practiced until recent years by the Jews of Djerba). In other communities, the henna was simply smeared thickly over the hands and feet.

At Jewish weddings in Amizmiz and Marrakech in the early 20th century, women would throw henna in the corners of the room so that the jnun would not be jealous of the bride; they would ask the jnun to do no harm to the bride, and to take the henna for themselves. In Sefrou, if a Jew was being negatively affected by a spirit, they would prepare an offering known as ‘ar [a form of contract that obliges service], consisting of henna, coriander, oil, and a scarf, and offer it to the spirit, saying: “I offer this ‘ar to you because I have wronged you. I am just like one of your children. Forgive me and pardon me. The coriander is for you, and the henna is for your children” (similarly, Algerian Jews also used henna to help someone who had fallen ill because of the negative influence of a spirit or bad jinn).

At Jewish weddings in Amizmiz and Marrakech in the early 20th century, women would throw henna in the corners of the room so that the jnun would not be jealous of the bride; they would ask the jnun to do no harm to the bride, and to take the henna for themselves. In Sefrou, if a Jew was being negatively affected by a spirit, they would prepare an offering known as ‘ar [a form of contract that obliges service], consisting of henna, coriander, oil, and a scarf, and offer it to the spirit, saying: “I offer this ‘ar to you because I have wronged you. I am just like one of your children. Forgive me and pardon me. The coriander is for you, and the henna is for your children” (similarly, Algerian Jews also used henna to help someone who had fallen ill because of the negative influence of a spirit or bad jinn).

|

Jews in Morocco considered the henna plant to have certain qualities of protection and blessedness, similar to what their Muslim neighbours termed baraka. Jewish homes in Morocco would often have a hamsa, or stylized hand, drawn on the wall in henna to protect the inhabitants of the home. Before moving into a new house, Jews in Tlemcen (eastern Morocco) would sprinkle henna powder in the four corners of each room and leave it there overnight to pacify any spirits which were inhabiting the building, so that they would allow their human tenants to live with them in peace. This custom was practiced among Algerian Jews as well.

|

Sources and References:

Ben-Ami, Issachar. 1974 Le mariage traditionnel chez les Juifs marocains [The Traditional Marriage among Moroccan Jews]. In Studies in Marriage Customs.

Benchimol, Isaac. 1888 Les Juifs de Tetuan: les moeurs et coutumes religieuses [The Jews of Tetouan: their religious customs and rituals]. Bulletin d’Alliance Israelite Universelle.

Bitton, Eliyahu. 1998 Netivot haMa‘arav: minhagei Maroqo [Western Paths: customs of Morocco].

Chetrit, Joseph. 2003 Tiqsei haḥinna baḥatuna hayehudit baMaroqo vehitḥadshutam beYisrael [Henna ceremonies in the Jewish wedding in Morocco and their revival in Israel]. In Haḥatuna hayehudit hamesoratit baMaroqo [The Jewish Traditional Marriage in Morocco].

Dar‘i, Yehuda. 2003 Haḥatuna hayehudit baqehilot kefariyyot: minhagei nissu’in b’Ighil n- Ughu [Jewish Marriage in Rural Communities: wedding customs in Ighil n-Ughu]. In Haḥatuna hayehudit hamesoratit baMaroqo [The Jewish Traditional Marriage in Morocco].

Herber, Jean. 1929 Peintures corporelles au Maroc: les peintures au ḥarqus [Body painting in Morocco: paintings with ḥarqus]. Hespéris, Vol. 9 No. 1.

Lemprière, William. 1793 A Tour from Gibraltar to Tangier, Sallee, Mogadore, Santa Cruz, Tarudant; and Thence Over Mount Atlas, to Morocco: Including a Particular Account of the Royal Harem, &c.

Malka, Elie, and Louis Brunot. 1940 Textes judéo-arabes de Fes [Judeo-Arabic texts of Fes].

Malka, Elie. 1946 Essai d’ethnographie traditionnelle des Mellahs: ou croyances, rites de passage, et vieilles pratiques des Israélites marocains [An attempt at a traditional ethnography of the mellahs: or beliefs, passage rituals, and old customs of Moroccan Jews].

Romanelli, Samuel. 1926 [originally published 1792] Massa‘ ba‘Arav, hu sefer haqorot [Travail in an Arab Land: that is, the book of journeys].

Scott, Colonel. 1842 A journal of a residence in the Esmailla of Abd-el-Kader and of travels in Morocco and Algiers.

Slouschz, Nahum. 1927 Travels in North Africa.

Stillman, Norman. 1983 Women on Folk Medicine: Judaeo-Arabic Texts from Sefrou. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 103, No. 3.

Stillman, Yedida Khalfon. 1970 The Evil Eye in Morocco. Israel Folklore Research Centre Studies.

Willner, Dorothy, and Margot Kohls. 1962 Jews in the High Atlas Mountains: a partial reconstruction. Jewish Journal of Sociology, Vol. IV, No. 2.

Zafrani, Haïm. 2000 Two Thousand Years of Jewish Life in Morocco.

Benchimol, Isaac. 1888 Les Juifs de Tetuan: les moeurs et coutumes religieuses [The Jews of Tetouan: their religious customs and rituals]. Bulletin d’Alliance Israelite Universelle.

Bitton, Eliyahu. 1998 Netivot haMa‘arav: minhagei Maroqo [Western Paths: customs of Morocco].

Chetrit, Joseph. 2003 Tiqsei haḥinna baḥatuna hayehudit baMaroqo vehitḥadshutam beYisrael [Henna ceremonies in the Jewish wedding in Morocco and their revival in Israel]. In Haḥatuna hayehudit hamesoratit baMaroqo [The Jewish Traditional Marriage in Morocco].

Dar‘i, Yehuda. 2003 Haḥatuna hayehudit baqehilot kefariyyot: minhagei nissu’in b’Ighil n- Ughu [Jewish Marriage in Rural Communities: wedding customs in Ighil n-Ughu]. In Haḥatuna hayehudit hamesoratit baMaroqo [The Jewish Traditional Marriage in Morocco].

Herber, Jean. 1929 Peintures corporelles au Maroc: les peintures au ḥarqus [Body painting in Morocco: paintings with ḥarqus]. Hespéris, Vol. 9 No. 1.

Lemprière, William. 1793 A Tour from Gibraltar to Tangier, Sallee, Mogadore, Santa Cruz, Tarudant; and Thence Over Mount Atlas, to Morocco: Including a Particular Account of the Royal Harem, &c.

Malka, Elie, and Louis Brunot. 1940 Textes judéo-arabes de Fes [Judeo-Arabic texts of Fes].

Malka, Elie. 1946 Essai d’ethnographie traditionnelle des Mellahs: ou croyances, rites de passage, et vieilles pratiques des Israélites marocains [An attempt at a traditional ethnography of the mellahs: or beliefs, passage rituals, and old customs of Moroccan Jews].

Romanelli, Samuel. 1926 [originally published 1792] Massa‘ ba‘Arav, hu sefer haqorot [Travail in an Arab Land: that is, the book of journeys].

Scott, Colonel. 1842 A journal of a residence in the Esmailla of Abd-el-Kader and of travels in Morocco and Algiers.

Slouschz, Nahum. 1927 Travels in North Africa.

Stillman, Norman. 1983 Women on Folk Medicine: Judaeo-Arabic Texts from Sefrou. Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 103, No. 3.

Stillman, Yedida Khalfon. 1970 The Evil Eye in Morocco. Israel Folklore Research Centre Studies.

Willner, Dorothy, and Margot Kohls. 1962 Jews in the High Atlas Mountains: a partial reconstruction. Jewish Journal of Sociology, Vol. IV, No. 2.

Zafrani, Haïm. 2000 Two Thousand Years of Jewish Life in Morocco.

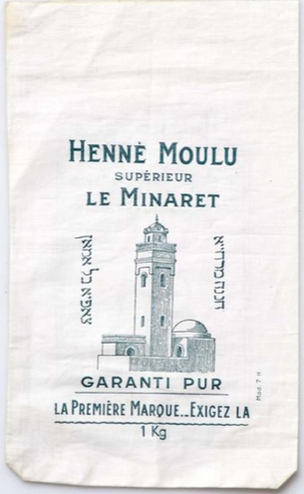

Pictures from:

Sylvain, Gerard. 1980 Images et traditions juives: un millier de cartes postales (1897-1917) pour servir à l'histoire de la diaspora [Jewish images and traditions: a thousand postcards (1897-1917) to serve for the history of the diaspora].

Westermarck, Edward. 1904 The Magic Origin of Moorish Designs. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 34.

The Museum of Jewish Moroccan Heritage, www.judaisme-marocain.org.

Westermarck, Edward. 1904 The Magic Origin of Moorish Designs. The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 34.

The Museum of Jewish Moroccan Heritage, www.judaisme-marocain.org.