This information is the result of my own research: please contact me if you have questions, or would like further clarification or direction to sources. Please do not copy this information without proper citation.

Henna in the Middle Ages

After the rise of Islam in the 7th century CE, henna became a significant export for the rapidly-expanding Muslim world through much of the Middle Ages. Henna continued to be used medicinally: it appears in medieval prescriptions, materia medica lists, and other medical documents. The famous 12th-century Jewish doctor Maimonides mentions henna as a beneficial compress for insect stings. Compilations of traditional Islamic medicine, such as the 14th-century work Tibb an-Nabawi [The Medicine of the Prophet] of ibn Qayyim al Jawziyya, mention henna as a beneficial treatment for headaches and muscular pains, a poultice for burns and blisters, and good for strengthening nails and hair. Jewish merchants, already known for their international commerce, traded in henna and indigo across the Mediterranean; the henna trade is referenced in the letters of eleventh-century Jewish Levantine merchants from the Cairo Geniza [a vast collection of Jewish and Karaite manuscripts, spanning religious documents, business transactions, and personal correspondance from the 9th to 19th centuries CE, found in the Ben Ezra synagogue in Cairo], and in the documents of the Cairo Genizah, among the names of Jewish merchants derived from their professions, we find merchants of paints (Asbaghi) and indigo (Khidabi), and the name Hinnawi, ‘henna dealer’ or ‘henna siever’. Henna was grown throughout North Africa, southern Spain, and the Mediterranean basin. In the 13th century, Jewish dyers were brought from Djerba by Emperor Frederick II and granted land in Sicily to grow henna and indigo.

Henna was used in the medieval Mediterranean by Jews, Christians, and Muslims. The author of De Ornatu Mulierum [On the Adornments of Women, the third part of an eleventh-century Christian medical compendium, the Trotula, written in Salerno, in southern Italy], described henna as a soothing ointment to apply after depilating, especially if the pubic area was irritated, and henna was recommended as a hair dye. The Spanish Muslim traveller and historian ibn Jubayr noted in 1184: “The Christian women of [Palermo] follow the fashion of Muslim women... They go forth on this Feast Day [Christmas] dressed in robes of gold-embroidered silk... bearing all the adornments of Muslim women, including jewellery, henna on the fingers, and perfumes”. Hennaed fingers and nails can be seen depicted in many illuminated manuscripts from this period, both religious and secular.

|

There is a rare depiction of what appear to be two hennaed drumheads in the Golden Haggada [an illuminated ritual prayer guide for the Passover meal from northern Spain, most likely Barcelona, circa 1320], held by Miriam and an Israelite woman.

The image shows the women holding traditional frame drums, with brownish-red patterns; the square adufe drum has an eight-pointed star on the center, and the round pandero drum has a swirling pattern around its edge. It is likely that this represents henna; the colour is accurate, henna will stain a leather drumhead and will not flake off (as paint would), and henna has been used to stain drumheads in North Africa into the present day. The illustrator of this manuscript took care to depict not just any drum, but one that was used by contemporary Jewish female minstrels. In fact, the square frame drum was a specific symbol of Jewish women, and Miriam in particular, in medieval iconography. Since the artist chose so carefully to depict realistically a drum that would be easily recognizable to the contemporary Jewish readers of the haggada, it can be suggested that drumheads were commonly hennaed in medieval Iberia, or at least that it would not be unusual to see a drumhead hennaed with patterns played by a Jewish musician. |

Assuming that this represents henna, this is one of the earliest depictions anywhere of patterned henna, and one of the few visual depictions of Jewish henna in medieval Iberia. Unfortunately, given the paucity of Jewish manuscripts that have survived from medieval Spain, it is impossible to tell how widespread the practice was, or if similar patterns were done on skin as well; the women in the Golden Haggada do not appear to be hennaed.

In this period, we find evidence that henna was used in Jewish pre-wedding ceremonies, in marriage documents that mention the henna ceremony in the enumeration of the costs that the groom’s family was responsible for paying, along with the bride’s dress, and jewelry. While some 10th-century Persian poetry refers to the beauty of a bride's hennaed hands, these documents are the earliest explicit reference that we have to the existence of a ceremony of hennaing the bride as part of the preparations for the wedding. For example, the following marriage contract from the thirteenth century testifies that the groom will pay for the henna and bridal costume ‘as customary’ (translation by Shlomo Goitein):

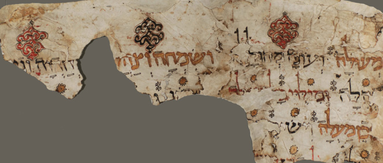

Fragment of a 12th-century ketuba [wedding certificate] from Egypt

We, the undersigned, testify that the following happened in our presence on the tenth of Nisan, 1554, of the Era of the Documents [April 2, 1243 CE] here in Fustat of Egypt, which is situated on the Nile River. Mr. Joseph, the esteemed young man, may his end be blessed, son of Mr. Abraham, the esteemed elder, may his end be blessed, engaged and contracted a marriage with Rebekah, the bride, the mature virgin, daughter of Abraham, the esteemed elder, the honoured almoner [synagogue official in charge of social welfare], may his end be blessed, and undertook to pay her 10 dinars [gold coin] as her first instalment, plus the cost of the Henna, the khuyut [headdress], and other expenses, as is customary. Rebekah confirmed that she had received on account 5 of the 10 dinars as a first instalment... We have written down what we have witnessed, and signed and delivered the document into the hands of the aforementioned Rebekah, so that it may serve her as a proof and title of right. [Signed by the prominent judge Immanuel ibn Yehiel].

There are many references to women with reddened fingers or dyed fingernails in Hebrew poetry from medieval Spain; it can be reasonably assumed that this refers to henna, given that henna was readily available in medieval Spain, that there were no other substances available in this period to dye skin a reddish colour, and that we have textual and pictorial evidence supporting the use of henna as a dye in this time.

In the poetry, the red of the woman’s hennaed fingertips is often used metaphorically for the blood of the lover’s heart; the association of henna with the lover’s blood was a common image in both Muslim and Jewish poetry. For example, Yehuda haLewi laments his cruel lover (translation by Scheindlin 1999):

In the poetry, the red of the woman’s hennaed fingertips is often used metaphorically for the blood of the lover’s heart; the association of henna with the lover’s blood was a common image in both Muslim and Jewish poetry. For example, Yehuda haLewi laments his cruel lover (translation by Scheindlin 1999):

Bear my greetings, mixed with tears

Mountains, hills - whoever hears -

To ten lovely fingernails

Painted with blood from my entrails;

To eyes mascaraed with black dye

From the pupil of my eye.

Though she’ll never call me dear,

Maybe she’ll pity me for my tear.

Mountains, hills - whoever hears -

To ten lovely fingernails

Painted with blood from my entrails;

To eyes mascaraed with black dye

From the pupil of my eye.

Though she’ll never call me dear,

Maybe she’ll pity me for my tear.

There was a custom among Egyptian Jews in the Middle Ages to hold a grand bridal procession from the betrothal hall to the synagogue, where the bride and her maidens led the procession dressed as men with helmets and swords, while the groom and his youths were dressed in women's clothing and jewelry, and had their hands hennaed.

This was apparently related to a similar contemporary phenomenon: effeminate young Jewish boys who dyed their hands with henna and put kohl under their eyes, spoke in feminine voices, arranged their hair in curls, and wore women’s clothing.

This was apparently related to a similar contemporary phenomenon: effeminate young Jewish boys who dyed their hands with henna and put kohl under their eyes, spoke in feminine voices, arranged their hair in curls, and wore women’s clothing.

The rabbis did not approve of these practices — both the men wearing women’s clothing/henna and the women dancing in public in front of men — and the great sage Maimonides strongly objected to it, which appears to have put an end to the practice.

However, the phenomenon of beautiful pre-pubescent boys, often hennaed, who worked as dancers and public performers, continued in Jewish communities in the Muslim world until the present-day.

In the 19th century, Edward Lane noted that there were dancers in Egypt known as ghawals or ginks (from the Turkish çengi): effeminate boys dressed as women, with henna and kohl. We have records of similar dancers in the Rif and Atlas Mountains of Morocco, in Turkey, in Iran/Afghanistan, and throughout Central Asia, up until the mid-20th century. Throughout, henna appears as a consistent and visible marker of their status as 'gender-variant': sometimes they were indistinguishable from girls (to the Western, colonial eye), but generally it was commonly known that they were male-bodied, but presenting with many of the markers of feminine identity. These dancing boys were also most often Jewish (although in some areas they may also have been Greeks, Armenians, or Gypsies/Roma).

However, the phenomenon of beautiful pre-pubescent boys, often hennaed, who worked as dancers and public performers, continued in Jewish communities in the Muslim world until the present-day.

In the 19th century, Edward Lane noted that there were dancers in Egypt known as ghawals or ginks (from the Turkish çengi): effeminate boys dressed as women, with henna and kohl. We have records of similar dancers in the Rif and Atlas Mountains of Morocco, in Turkey, in Iran/Afghanistan, and throughout Central Asia, up until the mid-20th century. Throughout, henna appears as a consistent and visible marker of their status as 'gender-variant': sometimes they were indistinguishable from girls (to the Western, colonial eye), but generally it was commonly known that they were male-bodied, but presenting with many of the markers of feminine identity. These dancing boys were also most often Jewish (although in some areas they may also have been Greeks, Armenians, or Gypsies/Roma).

The End of Henna in al-Andalus

Henna, as a practice symbolic of Jewish and Muslim culture, was one of the things outlawed as Christians reconquered the Iberian peninsula in the 15th century CE, along with refraining from pork and wine. Henna use is a ritual behaviour that is visible on the body and not immediately removable; thus, it was a perfect charge against someone suspected of hiding Muslim or Jewish heritage. Henry Lea records that in 1530 the Bishop of Guadix attempted to ban henna use but the women of the city complained, supported by the Captain-General Mondéjar, who told the bishop that it had nothing to do with faith; in 1543, Mari Gomez la Sazeda was arrested for henna use but she pleaded that henna use was not a specifically Moorish custom, saying that non-Muslim women also frequently stained their hands and hair with henna. Ultimately, the 1566/1567 pragmatica [royal decree] of Philip II not only forbade the use of henna and the wearing of Moorish-style clothing, but also decreed that marriage ceremonies and feasts must conform to Christian custom, and must take place with open doors to allow magistrates to enter and inspect the proceedings.

Sources and References:

Abrahams, Israel. 1896 Jewish Life in the Middle Ages.

Amar, Zohar, and Efraim Lev. 2008 Practical materia medica of the medieval eastern Mediterranean according to the Cairo Genizah.

Ben Sasson, Menahem. 1999 Yehudei Sitzilia 825-1068: te‘udot umeqorot [The Jews of Sicily, 825-1068: documents and sources].

Broadhurst, Ronald. 1950 The travels of Ibn Jubayr, being the chronicle of a mediaeval Spanish Moor concerning his journey to the Egypt of Saladin, the holy cities of Arabia, Baghdad the city of the caliphs, the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, and the Norman kingdom of Sicily.

Glick, Thomas. 2005 Islamic and Christian Spain in the early Middle Ages.

Goitein, Shlomo. 1967 A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, vols. I-IV.

Green, Monica. 2002 The Trotula: an English translation of the medieval compendium of women's medicine.

Harvey, John. 1992 Garden Plants of Moorish Spain: a fresh look. Garden History, Vol. 20, No. 1

Lea, Henry. 1968 The Moriscos of Spain: their conversion and expulsion.

Mentré, Mireille. 1996 Illuminated Manuscripts of Medieval Spain [originally Le Peinture Mozarabe, trans. by Jenifer Wakelyn].

Molina, Mauricio. 2010 Frame drums in the medieval Iberian Peninsula.

Murray, Stephen, and Will Roscoe. 1997 Islamic Homosexualities: culture, history, and literature.

Perles, Joseph. 1875. Jewish Marriage in Post-Biblical Times: a study in archaeology. In Hebrew Characteristics: Miscellaneous papers translated from the German. New York: Jewish Publication Society. Originally published in 1860: Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judenthums.

Rosen, Tova. 2003 Unveiling Eve: reading gender in medieval Hebrew literature.

Roth, Norman. 2003 Medieval Jewish Civilization: an encyclopedia.

Roth, Norman. 2005 Daily Life of the Jews in the Middle Ages.

Scheindlin, Raymond. 1999 Wine, Women, and Death: medieval Hebrew poems on the good life.

Schippers, Arie. 1994 Spanish Hebrew Poetry and the Arab Literary Tradition: Arabic themes in Hebrew Andalusian poetry.

Simonsohn, Shlomo. 1997 The Jews in Sicily: 383-1300.

Williams, John. 1977 Early Spanish Manuscript Illumination. New York: George Braziller.

Amar, Zohar, and Efraim Lev. 2008 Practical materia medica of the medieval eastern Mediterranean according to the Cairo Genizah.

Ben Sasson, Menahem. 1999 Yehudei Sitzilia 825-1068: te‘udot umeqorot [The Jews of Sicily, 825-1068: documents and sources].

Broadhurst, Ronald. 1950 The travels of Ibn Jubayr, being the chronicle of a mediaeval Spanish Moor concerning his journey to the Egypt of Saladin, the holy cities of Arabia, Baghdad the city of the caliphs, the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem, and the Norman kingdom of Sicily.

Glick, Thomas. 2005 Islamic and Christian Spain in the early Middle Ages.

Goitein, Shlomo. 1967 A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza, vols. I-IV.

Green, Monica. 2002 The Trotula: an English translation of the medieval compendium of women's medicine.

Harvey, John. 1992 Garden Plants of Moorish Spain: a fresh look. Garden History, Vol. 20, No. 1

Lea, Henry. 1968 The Moriscos of Spain: their conversion and expulsion.

Mentré, Mireille. 1996 Illuminated Manuscripts of Medieval Spain [originally Le Peinture Mozarabe, trans. by Jenifer Wakelyn].

Molina, Mauricio. 2010 Frame drums in the medieval Iberian Peninsula.

Murray, Stephen, and Will Roscoe. 1997 Islamic Homosexualities: culture, history, and literature.

Perles, Joseph. 1875. Jewish Marriage in Post-Biblical Times: a study in archaeology. In Hebrew Characteristics: Miscellaneous papers translated from the German. New York: Jewish Publication Society. Originally published in 1860: Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judenthums.

Rosen, Tova. 2003 Unveiling Eve: reading gender in medieval Hebrew literature.

Roth, Norman. 2003 Medieval Jewish Civilization: an encyclopedia.

Roth, Norman. 2005 Daily Life of the Jews in the Middle Ages.

Scheindlin, Raymond. 1999 Wine, Women, and Death: medieval Hebrew poems on the good life.

Schippers, Arie. 1994 Spanish Hebrew Poetry and the Arab Literary Tradition: Arabic themes in Hebrew Andalusian poetry.

Simonsohn, Shlomo. 1997 The Jews in Sicily: 383-1300.

Williams, John. 1977 Early Spanish Manuscript Illumination. New York: George Braziller.